Credit: Isabella Parish

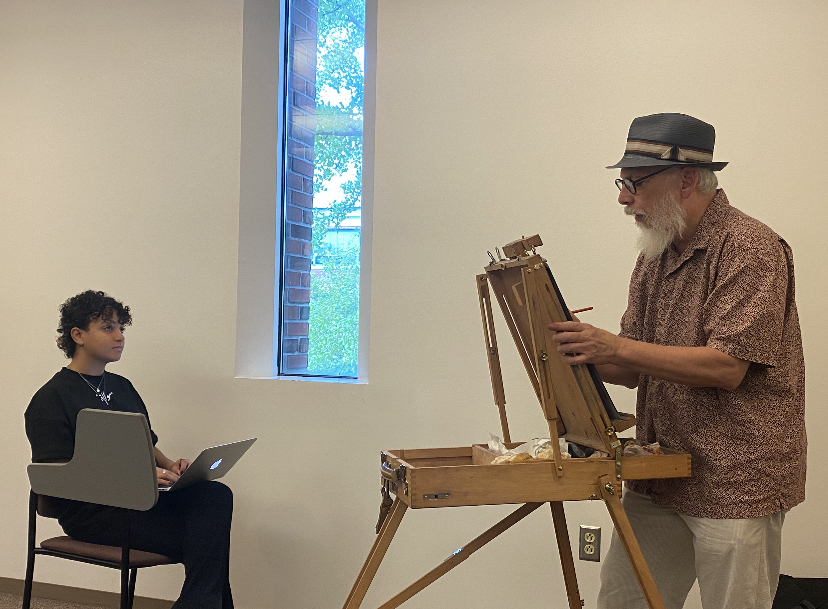

Every time someone sits down in front of his canvas, Brian Simpson tells his subject the same thing.

“Point your nose at me, and don’t point it anywhere else.”

Posing for a portrait is an intimate social experience between the artist and the subject. The dynamic that Simpson has with his clients is similar to that of a barber and someone getting their haircut—the physical closeness that these services demand promotes conversation. In the case of portrait drawing though, the artist and the subject face each other the whole time. It’s even more personal.

Simpson enjoys talking to the people he draws.

As his first subject sits and prepares to be drawn, Simpson carefully clips his drawing paper to his French easel and takes count of his colored charcoal. With an instinctive stroke of his wispy white beard and quick adjustment of his fedora, he focuses his discerning gaze on the face in front of him.

“Part of this is art, and part of it is conversation,” he explains. First I’ll usually ask you something like, ‘what’s your major?’ And your major is..?”

“Marketing,” she replies. He lifts his charcoal pencil to eye level, superimposing it on her face to get an idea of her facial dimensions.

“Marketing! Well then I’d say something like this: That’s a really important major, especially from an artist’s point of view. We all get our degrees and they send us out into the world, and we don’t know what the hell to do. We’re suddenly self-employed and have no idea where to go from there.”

Simpson grew up in Creve Coeur, a small factory town on the outskirts of Peoria, Illinois. The town of a few thousand was mostly populated by blue-collar types, which wasn’t a lifestyle that interested Simpson much—he wanted to make art. He enjoyed making posters of bands for his brothers growing up, but art wasn’t seen as a particularly valuable talent in the ’60s and ’70s in Creve Coeur. The sides of company conversion vans needed to be painted, but beyond that, the art scene there was miniscule.

In 1975 Simpson decided to enroll in the art program at Illinois Central College, a community college in East Peoria. There he blossomed as a young artist, refining his ability to draw the human figure in life-drawing classes before moving on to Illinois Wesleyan University in the fall of 1977.

When he graduated from IWU in 1979 with a BFA in Art and Photography, Simpson was faced with a profound but common problem that many college graduates experience.

Once Simpson was out in the world, he didn’t know what to do. That is– besides making art.

He spent the next two years living at home creating works of art in his parents’ basement and working a teaching job at a local community college.

Illinois State offered him a tuition waiver to pursue a Master’s Degree in Art History and Photography, beginning in 1981. Maybe this was it, he thought. If he went to graduate school he could teach art in a university.

Once he got to Illinois State, it wasn’t at all what he expected. Standards were rigid, and professors were intent on limiting the scope of art he could create and explore. His art had to be technically sound, and by the book. He just wanted to make things that were beautiful, but that was rarely enough for his instructors. Why make something beautiful if there’s no deeper artistic statement to analyze and deconstruct?

The head of the photography department had him in his office once a week to tell him his artwork was too “out there.” He took a drawing class where the instructor asked him to scratch on glass and expose that on paper, and when he elected to do his own thing instead, he got a B. It was an insult to get a B as a grad student– he felt it was his punishment for not doing what the instructor wanted him to do.

His anger and resentment peaked with his final art show. The day of the show, he was ready for the barrage of critiques and judgments that were sure to come his way. He was ready for a fight. His committee came to look at his art, and to his surprise, he wasn’t met with arguments, or technical critiques or criticism on the intellectual basis of his art. He was met with praise. “This is great Brian, it’s wonderful,” they exclaimed.

Only he didn’t breathe a sigh of relief. He got angrier. Why put him through hell all this time, only to validate him now?

Simpson tried to write his final thesis, but couldn’t forget the horrible experiences he had and the grievances he harbored, and it morphed into a denunciation of the academic system. He never submitted his thesis. Simpson asked himself if he really needed that piece of paper his diploma was printed on, and when he decided he didn’t, he walked away.

Burned out and unsure if he’d ever make art again, Simpson spent the next year-in-a-half in a personal and creative rut.

After some time on a bar stool during that uncertain period of his life, he decided to pursue interests he had outside of academia, and for him, business had always come pretty easy. He opened up a vintage clothing store in Bloomington, and a few years later decided to focus his efforts instead on owning a bookstore. He bought Babbitt’s Books in November of 1989.

What finally brought him back to art, funnily enough, was a sort of burnout from the bookstore. The 60-hour work weeks and the market disruption that forced him to change his business plan every three years or so was starting to weigh on him.

Simpson started to create art again as a distraction from that work. He went back to the basics—just charcoal and paper. He returned to life drawing as he did back at ICC, and started a Tuesday Night Drawing Group at a Bloomington art studio. He wasn’t making art for a grade, so he didn’t need a deep artistic statement. He was creating art again for the sake of creating art. He was creating things that he thought were beautiful, and that was that.

Simpson sold the bookstore in 2015 after 25 years in business, and a weight was lifted off his shoulders. Now he had more time to create the type of art he wanted to create. He started to focus on portraits. They’re quick and easy– he simply sets up shop in the hustle and bustle of a fair, or festival or other community event, and people line up to get a composite of their face drawn in 15 to 20 minutes. When people sit down with him for that short of a period, something kind of amazing happens, Simpson said.

People open up.

When they’re being drawn they start to tell him things– where they come from, what their hopes are, how they see the world, and what matters to them. What he finds so fulfilling about the interactions of portrait drawing isn’t necessarily what people say when they’re being drawn. It’s the feeling he gets from their company. To Simpson, It’s like the comfort you feel sitting in front of a fireplace– you probably wouldn’t recall the specific circumstances of the nicest fire you’ve ever felt, but the feeling of warmth you got from it certainly stays with you.

Most of the people he draws are regular working class people like the ones he grew up with in Creve Coeur. People he didn’t always get along with, nor share the same beliefs and interests. Some remind him of people he despised. Yet, art reveals a shared humanity that Simpson gleans when he recreates the little nuances of people’s faces on his paper. It gives him a full feeling, the kind that creates a lump in his throat after a day of drawing. The kind that washes away the disappointment and anger of his graduate school days.

He just surpassed his one-year anniversary as a partial owner in Main Gallery 404 in downtown Bloomington, a gallery that showcases the artwork of local artists. At the gallery he gets to talk to customers over the counter again, something he misses from his days as a bookstore owner.

Simpson doesn’t impose intellectual meaning on his work, mostly because he doesn’t care. He’s too old to care. Art for him is experiential. He connects to the people he draws, and through them, creates art that’s fulfilling to him. People tend to really like his portraits, and that’s where the real payoff lies. To some people, being given their first piece of real original art is a profoundly important experience, and Simpson can feel it. The smile on their face when they look back at their sketched face lets him know that all of the detours and roadblocks were worth it. His love for art is alive again, and it’s here to stay.